This exquisite history celebrates the enduring, pivotal role of the working drawing

Ever since Leon Battista Alberti postulated the primary authority of the drawing set – of plan projections drawn by an ‘architect’ representing his ‘idea’ – the privilege of invention and planned intent was sundered from the artisans and builders who had until the 15th century imagined and implemented their built structures on site, as they were made. Drawn information, the very foundation of architecture as a profession, is also a place of profound longing for a lost state. Like Aristophanes‘ story that man was originally cleaved in half by Zeus, and that all of us are but half of one split whole, and are doomed to spend our lives searching for our long lost other in pursuit of an impossible unity, so it is with architecture. The site, the builders, the artisans and the makers are on one side of the historic divide, and architects are on the other. Where Aristophanes’ humans engage in fraught, never complete relationships bound by ‘love’ between pairs of individuals in pale imitation of an original unity, so architects and builders repeatedly unite in never complete, fraught and complex relationships, bound by their working drawings.

The Working Drawing: The Architect’s Tool, edited by Annette Spiro and David Ganzoni, is a beautiful paean to this complex relationship. A powerful sense of longing for that lost role – for the materiality, craftsmanship, the site and for the hand of the maker, embedded within the working drawing – emerges from this book. As the editors write, ‘When Sigurd Lewerentz draws masonry work, he “builds” the walls, as it were, with pencil on paper. One can positively smell the bricks.’ Severiano Mario Porto ‘draws the roof truss as though he would lay, with the pencil stroke, every rafter of the beams’. These phrases set the tone for a tactile and close look at the reproductions included within its pages. They speak eloquently of concern for the relatively small luxuries that such a modest project could provide in those times, whether it is Pier Luigi Nervi’s steel reinforcement drawing for the Palazzetto Dello Sport in Rome from 1957 – of which Nervi says ‘the form of steel reinforcement should always be aesthetic and give the impression of being a nervous system that brings to life the lethargic mass of concrete’ – or Lux Guyer’s housing complex for working women from 1925, with its five floors of meticulously drawn bathroom sanitaryware.

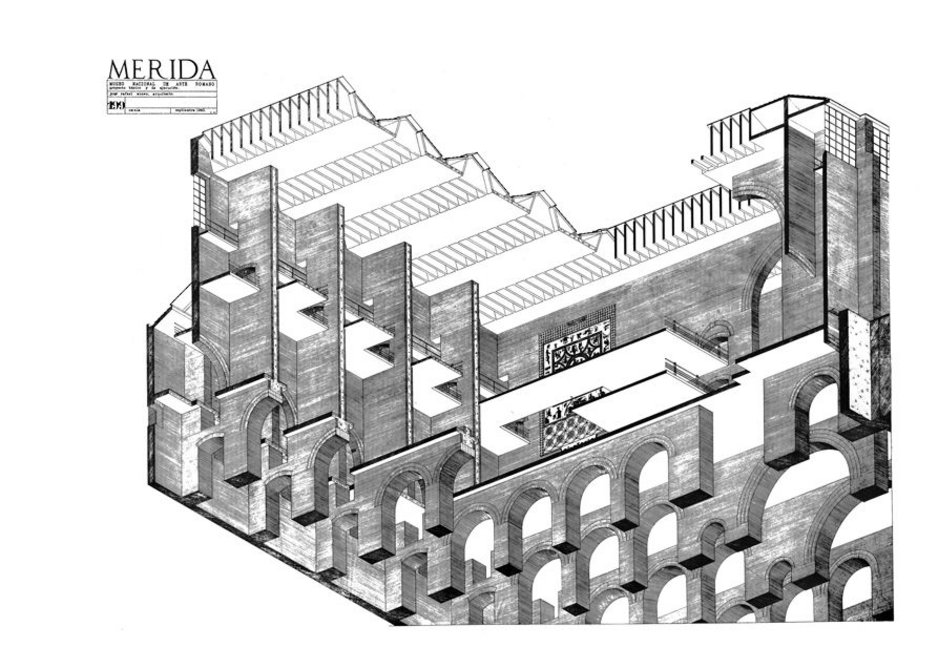

The Working Drawing is a beautifully presented, large format, 327 page hardcover book. It has 98 drawings each with their own double-page spread, reproduced in every case at the largest possible scale the format would allow, often with fold-out pages, and with a whole host of documentation types represented. These range from a vast 13th century elevation of Cologne Cathedral, through an engineer’s drawing by Mahendra Raj from 1980 of a concrete dia-grid roof structure in Srinagar, India, to a bricklaying computer script by Gramazio Kohler from 2006. The drawings are organised into 12 categories including ‘Measurement and Numbers’, ‘Building Elements’, and ‘Catalogue’. While these groups can sometimes feel rather uncomfortably forced, they each provide an opportunity for succinct and clearly phrased introductory texts which help to reiterate the main themes of the book in relation to the dizzying array of drawing types presented. The categories are followed by 12 essays by Herman Czech, Tom Emerson, Jonathan Sergison and others. The first six of these are outstanding as general commentaries on the subject, with the rest homing in on more specific subject matter – for instance the story of the planning for the Swiss Alpine way, the ‘Sustenstrasse’, and its absolutely remarkable topographic documentation.

There is an archival quality to the book with its thick paper and excellent print quality, the way it emphasises the scribbled note and rubbed-out line as much as anything else, a sense of deep concern that we should not forget the craftsmanship, and the act of making that was involved in many of these drawings. Ganzoni writes: ‘I feel the worn paper, smell the dust and heliographic print’s slight acidity,’ as he trawls the archives, and that ‘When looking at the plans, I can see the draftsperson at work: a pencil travels over the paper, an ink pen draws line after line, and a razor blade scrapes away the errors. Someone carefully coloured in an ink plan in the 19th century; another spent hours gluing on film after film of cross hatchings from behind a hundred years later; and a third labelled the header with a stencil.’

An opposite tendency is also found in these pages to celebrate the architect’s complex relationship with the maker. This is the attempt to negate the need for that relationship to exist at all, to erase the maker to some degree, reducing him or her to a pure extension of the perfect, totally complete drawing. Whether it is Spiro and Gantenbein saying of an air-pipe ‘One plan is not enough, above the plan header is a reference to seven additional plans for the same building elements’; or a plan by Helio Olga in which ‘there is an axonometric drawing for each single wood joint so that the tradespeople could place every screw in the right place accurately to the millimetre’; or the technological future where makers are robots and architects scriptwriters. In his essay ‘Future Plans’, Stephan Rutishauser dreams that ‘the building plan as a means of communication between architect and tradesperson will become an obsolete instrument, since the mediation between the two professions will no longer be necessary when the transformation to matter is carried out by a machine and the machine’s transformation code is written directly by the architect’. This is the prevailing, legally watertight tendency that is leading us towards a form of BIM in which the dream of this kind of perfect documentation comes true. Like Borges’ totally accurate map that was as big and detailed as the territory it depicted, 3D models may eventually become perfectly complete templates in every respect and at all scales, of a building that tradespeople will have to construct as a real facsimile of the digital original.

While this book could be seen as a nostalgic look at a soon-to-be-gone area of knowledge, it is full of a sense of confidence that this is not the case; that no matter what changes technology brings. As Tom Emerson put it in his essay Lines on Paper, The Enduring Language of Architecture: ‘Architecture continues to evolve within the present, dragging a past into the future full of conflicted meanings and associations’. He says: ‘Bricks remain bricky, even when laid by a robot borrowed from a car factory. Timber remains fibrous despite the scorched traces of the laser cutter,’ and so our information sets will always contain the marks of our working process, whether they are generated from a 3D BIM model, the infinite 2D space of Autocad, oil paper stretched out on our drawing desks, or the patched together pieces of parchments and quill of the renaissance. As we move yet again into new territory with our drawn information, this book is an exquisitely put-together, thoughtful reminder of how our profession always has and always will weave creativity, character, expression and depth into the precision and clarity of our drawn or modelled working information.

The Working Drawing: The Architect's Tool

Annette Spiro & David Ganzoni eds. Park Books 2014. £80 HB