Considered juxtapositions accentuate Andreas Gursky’s manipulation of what he sees in this self-curated retrospective

There’s a famous scene in Father Ted where Ted points out the window during a rural caravan holiday and explains to the feckless Father Dougal that the toy plastic cow he’s holding is ‘small, but that one is far away’. It’s a masterclass in comic absurdity, and one which touches on philosophical issues at the very core of Andreas Gursky’s work. For here, there are similar manipulations of scale, of flatness and depth of field, of artifice and reality, on display at this major retrospective of one of the world’s feted contemporary photographers – this inaugural show marking the reopening of FCBS’s refurbished and upgraded Hayward Gallery. It’s particularly satisfying to see the abstraction of his Rhein II – what was the world’s most expensive photograph – delicately lit in the upper galleries beneath its formerly contentious pyramid rooflights.

Gursky was born in 1955 in Leipzig to commercial photographer parents, and educated at the Folkwang University in Essen and then with Bernd and Hilla Becher in the shadow of Gerhard Richter at Düsseldorf Art Academy. He has has earned a reputation as the go-to chronicler of the Modern Age, with his huge scale representations of industrial infrastructure, corporate and commercial environments and mass socio-cultural interactions. Curiously it sits at odds with the slight, quietly spoken, casually dressed man at the press call, relating his difficulty with introducing display walls to the galleries to adequately represent his 40 years of output.

Seen here, Gursky seems initially a victim of his own success; the iconoclastic work he authored now regularly copied as a means of recording the global economy. But it’s in the interrogation of his images’ layers, when everything starts to be read in a different light, that Gursky the artist reveals himself. The show also tracks the chronological shift from analogue to digital and the seamless ease with which he moves from one to the other – along with the latter’s potential for infinite manipulation. As if to mark the moment, his 1995 Kodak is a pivot point for the show, his photo of the film giant’s Hong Kong HQ a last gasp of hubris – as toy-like and loaded as a Thomas Demand art piece and as disposable as one of its own empty film cartons. This is what happens, it warns us portentously, if you don’t move with the times.

Yet the show proves that Gursky didn’t need digital post-production to reveal himself as a master of scale and narrative – he was playing with the themes from the very outset. His early 1980s landscapes at first suggest unbridled nature in the manner of Romantic Caspar David Friedrich, before you register the human interventions; people dotted beside trees or riverbanks, garden furniture, rubbish, a motorway bridge in the distance. But these landscapes are for the most part reproduced small, restrained; counterpointed only by the empty heroic of his huge Ruhr Valley. It’s a photo preparing you for his massive Untitled I (1993), a close-up of the carpet in the Düsseldorf Kunsthalle, a contrapuntal amuse bouche before the enormous digital works that characterise his later output. As an aside, his 1995 Turner Collection re-presents three of Turner’s works on the walls of the Tate at apparent life-size; and Salerno I – for Gursky a key work – takes this city’s beauty, set on the Amalfi coastline, and through flattening the depth of field, objectifies it into the same terms of reference as its industrial port area in the foreground. Infrastructure as landscape, carpet as landscape; from here on in the artist no longer felt the need to make a distinction.

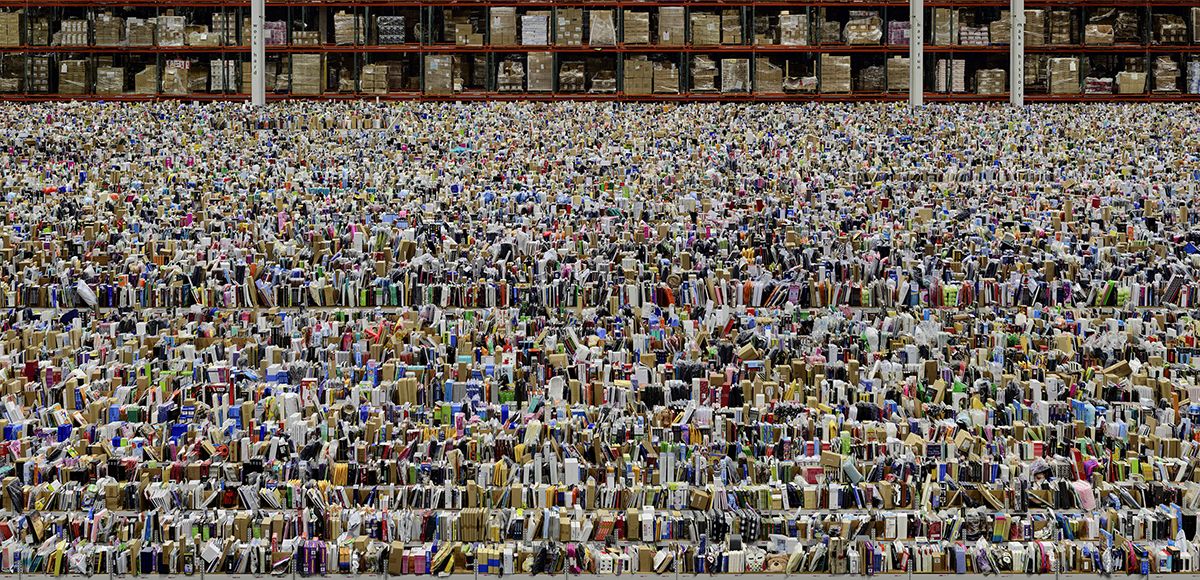

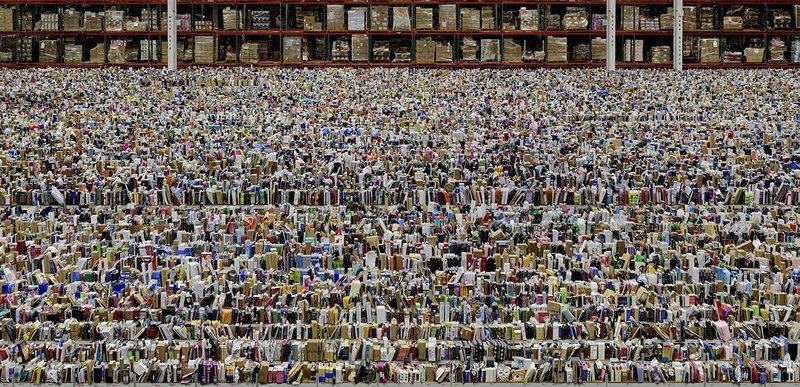

Gursky curated the show too, leading to engaging juxtapositions. The small Supernova sits beside the banal, enormous Unititled I; the massive store interior of 99 Cent (1999), a consumer’s dream, glares ironically across to his highly detailed, delicate satellite montage Antarctic (2010). A tiny image of a 2001 Madonna concert is like an Orthodox icon against the vast photo-fit scale of May Day IV (2000)’s German rave, while the fantasist delirium of the mass North Korean Arirang Festival, Pyongyang VI (2007) looks provocatively at Nha Trang (2004), hundreds of Vietnamese workers constructing wicker IKEA furniture – two state sanctioned collective ‘events’ at opposite ends of the political scale.

This last, with the abstraction of Rhein II and Almeria market gardening landscape El Ejido, placed together in such a way as you can barely tell where the Rhine’s waters stop and the polythene starts, marks a later stage in Gursky’s artistic development – one where he actually manipulates reality. In Rhein II he famously ‘disappeared’ a power station on its banks and in Nha Trang, he insisted on all the workers being dressed in orange. But it’s highlighted most clearly in the ‘made-up’ exhibition of Lehmbruck I, the benzene-addled, Last Supper doppelganger F1 Pit Stop I (2007) and Review (2015), four recent German chancellors fictionally brought together before a 1951 Barnett Newman Abstract Expressionist painting. Donald Trump might enjoy this last half of the show; it isn’t ‘fake news’ so much as Gursky’s belief that, within the context of art, this is all simply a new truth.

With so many complex contemporary themes picked up and layered in, this retrospective showcases the work of an artist at the peak of his powers. It’s almost a relief at the end to rest your eyes on Gursky’s recent mobile pics Utah and Tokyo, taken from a speeding car and train and blown up to enormous scale as if to reflect the phone’s inviolable cultural status. But though seeming nonchalantly shot, look again; Gursky denies us the simplicity we crave to the very last.

Andreas Gursky runs at the Hayward Gallery London from 25 January- 22 April 2018